Managing patient’s with borderline personality disorder (or emotionally unstable personality disorder) is something that myself and I know many of my colleagues find extremely challenging within the limits of primary care. I was therefore really looking forward to this session to gain a further understanding of the condition and learn from the experience and advice of two experts in this field.

The session was run by Dr Harriet Fletcher, a local consultant psychiatrist, and her colleague Annie Mason.

We began by discussing our thoughts on the definition of border line personality disorder (BPD). An extreme trait, often related to trauma, resulting in a difficulty in adapting to social situations, was agreed upon. It was also agreed that this label, although useful in allowing needs to be classified and defining allocation of services, can often be unhelpful for both medical staff and patients, as can lead to stigma and a feeling of helplessness. We discussed how this may reflect the fact that we often feel there is nothing we as clinicians can do to help. Encouragingly we learnt there has been studies that have shown those with symptoms of BPD can improve with treatment of rates reported up to 50%. Perhaps the frustration therefore is around accessing the right treatment for these patients in a timely manner. The controversy around labelling was similarly raised in the personality disorder consensus statement, that also highlighted the poor care and lack of access to services that patients often have to face, reflecting the groups experiences.

The aetiology of BPD appears to be complex and still unclear. There is a question around whether genetics play a part or whether it is purely developed based on early life experiences. There are clear links with issues with attachment at a young age, adverse childhood events and childhood trauma. There has also been recent evidence in neurobiology suggesting those with BPD may have structural changes resulting in a functional deficit in brain areas central in affecting emotional regulation.

There seems to be very limited research into BPD globally. In mental health services in the UK the prevalence is reported at around 50%. It is often assumed there are higher rates in women but numbers are in fact equal in the community. It was interestingly raised that there was no clear evidence of higher rates of BPD within areas of socioeconomic deprivation, although it was hypothesised this could be due to a lack of research, reporting or formal diagnosis in these areas.

We discussed the frustrations we felt in primary care, trying to access the appropriate services and support for these patients in the different areas we work in across Yorkshire and the Humber. There are very few BPD clinics across the UK, although in the NHS long term plan it outlined new funding for community mental health, including specific BPD services.

One area that we felt as GPs caused us significant anxiety when consulting with these patients was the management of their risk when assessing potential self-harm or suicidal episodes. 60-70% of those with BPD are reported to attempt suicide with 10% being successful. Those with a dual diagnosis such as personality disorder and drug dependence had higher rates of suicide.

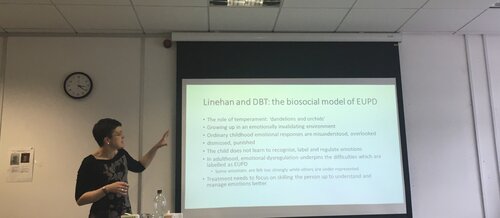

We moved on to talking about treatment. Psychotherapy is the process of teaching people to regulate their emotions. It involves stepping back, looking at situations from the outside and challenging what could be changed. We discussed the psychosocial factors that can be implemented in the development of BPD such as abuse, or biparental difficulties such as an absent father or over bearing mother. Interestingly the care givers response to abuse may be more important than the abuse itself in long term outcomes.

Attachment theory is also important. A useful analogy was used describing emotional health as an “elastic band” that needs testing in early life, but not too much! It is unsurprising people can develop difficulties in managing their emotions if they have never been taught how to do so. Often people can lack a sense of who they are and, as an infant gets older, the importance of an attachment figure as a secure base is paramount. The good news is however there is evidence that having a supportive attachment figure can override the effects of adverse childhood events.

CBT can also have a role in the management of those with BPD. This can take up to 36 sessions to be effective so is an intense commitment for the patient. It challenges the maladaptive schemas developed in childhood to cope with dysfunctional relationships with family members.

The session was very engaging with many experiences shared and much discussion around the topic. One of the questions raised was why as a population we seem to accept long waiting lists for mental health issues when they would be seen as inappropriate for physical issues. There was also debate around whether there should be space for an interim service between primary and secondary care mental health services as there was such a large gap between what can be provided by the two.

I found the session useful as it not only deepened my understanding of this topic but also taught me about the potentially positive outcomes for those with BPD. I often think about the prospective impact of traumatic life events on the future health of the young patients I see in surgery but learning about the positive effect a stable and supportive care giver can provide has left me feeling more optimistic. We need to continue to feedback to CCGS and other governing bodies about the need for wider and more accessible mental health services in our areas.

Useful resources:

– MIND – ebsite has a helpful, accurate patient information leaflet on BPD

– Oxford Mindfulness Centre – Free 8 week mindfulness course, accessible on website or through an app

– Headspace – Mindfulness app on monthly subscription

Dr Katie Burgass, Trailblazer GP 2018/19